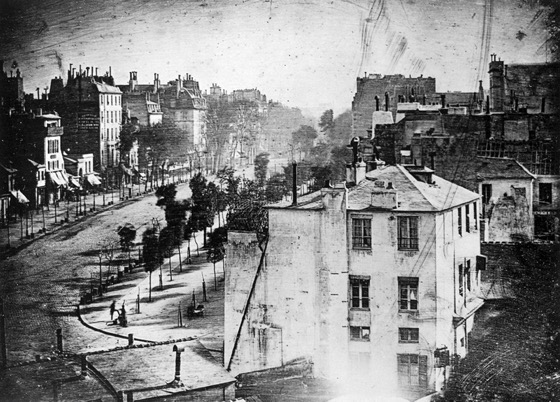

City streets seemed eerily empty in the early years of photography. During minutes-long exposures, carriage traffic and even ambling pedestrians blurred into nonexistence. The only subjects that remained were those that stood still: buildings, trees, the road itself. In one famous image, a bootblack and his customer appear to be the lone survivors on a Parisian boulevard. When shorter exposure times were finally possible in the late 1850s, a British photographer marveled: “Views in distant and picturesque cities will not seem plague-stricken, by the deserted aspect of their streets and squares, but will appear alive with the busy throng of their motley populations.”1

![Street Views via Cabinet [Shared]](http://welchwrite.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/shasta-daisy.jpg)